CDE will be closed on Monday, September 1, for the Labor Day holiday.

You are here

4.3 Structured Literacy

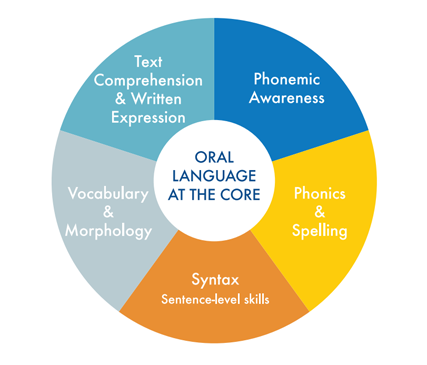

There has long been consensus among reading researchers, cognitive scientists, and those who have spent hundreds of hours teaching students with dyslexia that there is an approach to reading instruction that is based in science, uses evidence-based strategies and, most importantly, is effective. Structured Literacy is not a program but an approach to instruction that emphasizes the structure of language. These language structures include phonology (the speech sound system), sound/symbol associations, syllable structures, orthography (the writing system), syntax (the structure of sentences), morphology (the meaningful parts of words), semantics (word meaning and the relationship among words), and the organization of spoken and written discourse.

Structured Literacy teaches the essential components of reading/literacy as represented by the Literacy How Reading Wheel, which was introduced in Chapter 1: Introduction:

- Oral Language

- Phonemic Awareness

- Phonics and Spelling

- Vocabulary and Morphology

- Fluency

- Syntax

- Text Comprehension and Written Expression

While it is necessary that students are instructed in these essential content components, it is also critical that the delivery be evidence-based and consistent with the principles of effective instruction. Critical principles of effective instruction and intervention for students with dyslexia include the following:

Direct and Explicit Instruction: Structured Literacy instruction requires the deliberate and purposeful teaching of all concepts with continuous student teacher interaction. It is not assumed that students will naturally deduce these concepts on their own.

Systematic and Cumulative: Structured Literacy instruction is systematic and cumulative. Systematic means that the organization of the material follows the logical order of language. The sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic concepts and elements and progress methodically to those that are more difficult. Cumulative means each step must be based on concepts previously learned.

Diagnostic Teaching. The teacher must be adept at individualized instruction; that is, instruction must meet a student’s specific needs. The instruction is based on careful and continuous assessment — both informal (e.g., observation and all types of formative assessment) and formal (e.g., normed and standardized measures). The content presented must ultimately be mastered to the degree of automaticity. Automaticity is critical to freeing all the student’s attention and cognitive resources for comprehension and expression.

![]()

The IDA infographic What is Structured Literacy? offers a concise but complete explanation of the instructional elements and the evidence-based teaching principles of Structured Literacy.

Multisensory instructional strategies are a component of Structured Literacy. In fact, Structured Literacy has sometimes been referred to as multisensory language instruction. While the research on multisensory techniques is less robust than the research that validates other instructional principles, there exist strong clinical reports of the effectiveness of simultaneous use of visual, auditory, tactile-kinesthetic, and articulatory motor strategies during instruction. Examples include saying and writing a word simultaneously, tapping individual phonemes, and air-tracing.

Unfortunately, typically employed reading approaches such as guided reading or balanced literacy are not in and of themselves sufficient for struggling readers and not at all effective for students with dyslexia. These approaches do not provide sufficient or appropriate instruction in decoding and the essentials of the structure of language for struggling readers, including those with dyslexia. The IDA fact sheet Effective Reading Instruction for Students with Dyslexia explains that “what does work is Structured Literacy.”

For students with dyslexia, Structured Literacy plays an essential role in developing foundational reading skills in the areas of decoding, spelling, and the automatic recall of sight words. Structured Literacy must be delivered in addition to grade-level instruction for comprehension skills, vocabulary and content area knowledge. These important skills should be taught using accommodations, as needed, including differentiated materials and assistive technology. Accommodations and assistive technology are crucial in supporting student progress in meeting grade-level standards while developing lower-level foundational skills through Structured Literacy. Section 4.4 Accommodations and Assistive Technology provides additional information regarding accommodations and assistive technology.

Structured Literacy Use in Colorado

As pointed out earlier, Structured Literacy refers to an approach to teaching reading. It is not a program. While there are commercially published programs that are designed to meet the content criteria and instructional principles of Structured Literacy, this approach can be implemented effectively without the burden of purchasing a new reading program. Whether or not one uses a published program, comprehensive and explicit teacher training are essential to the implementation of Structured Literacy. Additionally, embedded coaching is strongly encouraged to enhance the fidelity of instruction.

In Colorado, the Exceptional Student Services Unit has used Structured Literacy as part of its federally mandated State Identified Measurable Result (SiMR), a required component of Colorado’s State Systemic Improvement Plan (SSIP). The Structured Literacy Project, initiated during the 2015-16 school year, has embraced the use of direct and explicit instruction in all essential components of early literacy instruction. Embedded within a multi-tiered system of supports, Structured Literacy lesson routines and strategies are used daily during whole group instruction (first-best instruction). Whole group instruction is supported with the inclusion of Structured Literacy reteach and practice during small group classroom instruction as needed. Additional instruction in Structured Literacy during targeted and intensive interventions has been shown to be most effective when aligned to classroom Structured Literacy instruction, when using the same scope and sequence of skills to be taught, and when incorporating consistent instructional language and routines.

Since Structured Literacy is an approach and not a specific program, schools participating in the CDE Structured Literacy Project have not had to purchase an additional published program. In order to ensure the delivery of a systematic and cumulative sequence of instruction, the CDE created a Structured Literacy Scope and Sequence for Grades K-3 and a series of grade-specific lesson routines. The Project has supported schools in ensuring that students have access to adequate resources for practice and connected text reading, including a range of decodable texts. Since Structured Literacy teaches reading and spelling as reciprocal skills, many schools have found they no longer need to purchase a separate spelling program. The Structured Literacy approach pairs nicely with a number of existing writing programs that utilize direct and explicit instruction in sentence, paragraph and compositional writing.

Factors Increasing the Effectiveness of Structured Literacy

Research has shown that Structured Literacy is effective. However, the effectiveness of a Structured Literacy instructional approach is contingent on a number of factors. Teachers must be provided with training in both the delivery of instruction and the content of instruction. (See Chapter 6: Support for Educators) In addition to ongoing training, teachers need access to specialists and coaches who can help them organize and deliver content using evidence-based strategies and who provide meaningful feedback about instruction. Lesson planning, daily lesson routines, corrective feedback, and lesson pacing must be done with fidelity, and instruction must offer frequent distributed practice with connected text. Teachers must understand how to use daily formative assessment to drive instruction and to inform their planning to meet the specific needs of each student. Teachers and interventionists need to collaborate and align their instruction along a continuum of time and intensity, using consistent instructional language and sequence of skills. Principals, as instructional leaders, need to create learning and teaching environments in which time for planning and collaboration is valued; data is gathered, discussed and used to inform instruction; and expectations that all students can learn are held and understood by teachers, parents, and students.

Having trouble with this webpage?

If you have problems with broken links or accessing the content on this page, please contact the Exceptional Student Services Unit at ESSU@cde.state.co.us. Please copy the URL link for this page into the email when referencing the problem you are experiencing.

Connect With Us